|

NORTHERN DEFENSE: THE WAR YEARS... AND SIGNIFICANT GROWTH

WARNING: This page is

graphically heavy. Please allow everything to load.

NOTE from Colleen: Though not every

aspect of the subject is covered, I have given more coverage to this chapter than many of the

others. The fact that this page will surprise (and hence, educate) many of

you is the reason. This is a page of history that seems to have been

pushed "under the rug" and because of it I wanted to place emphasis on the

incidents simply because they deserve to be known.

As this site develops, more will

be added to the War Years. You'll find notice of additions on the 'What's

New?' page. If you have material regarding Alaska in World War II that

you'd like to display here, please contact

me.

Prior to World War II, Alaska's only military establishment was old

Fort Seward in Haines, renamed Chilkoot Barracks in 1922. The post had been established during the gold rush days and was situated

where it could observe traffic bound inland over the Dalton Trail and over Chilkoot, Chilkat, and White passes. Eleven officers and 300 enlisted men

armed with Springfield rifles manned

the post. The installation did not have even a single antiaircraft gun.

The troops were immobilized because their only means of transportation consisted

of the tugboat Formance, needed serious engine repair. In essence,

the territory was indefensible.

In 1934, Delegate Anthony J. Dimond had recognized Japan as a threat

to America's security and asked Congress for military airfields and planes, a

highway to link the territory with the United States, and army garrisons.

Three years later, Dimond would warn his colleagues in the House of Representatives that Japanese fishermen

off Alaska's coast were actually disguised military personnel scouting out

information on Alaska's harbors, Dimond pleaded that Alaska was as much a key to

the Pacific as Hawaii and must be defended.

Early in 1935 Congress had named six strategic areas for

location of U.S. Army Air Corps bases. Alaska was one of these. The shortest

distance between the United States and Asia was the great circle route, 3,200

km (2,000 mi) north of fortified Hawaii but only 444 km (276 mi) south of the

Aleutians. Brigadier General Billy Mitchell, an advocate of air power,

testified before Congress in 1935 that Japan was America's most dangerous

enemy in the Pacific: "They will come right here to Alaska. Alaska is the most

central place in the world for aircraft, and that is true either of Europe,

Asia, or North America. I believe in the future he who holds Alaska will hold

the world, and I think it is the most important strategic place in the world."

In 1937 the Navy established its first seaplane base in the Territory

of Alaska on Japonski Island in Sitka. With

Japan fighting in Asia, plans were made to expand the military presence in Alaska. On October 1st,

1939 the seaplane base formally became a Naval Air Station. It was the first

of only three defending Alaska. The others were at Kodiak and Dutch Harbor.

The air station in Sitka was upgraded to Naval Operating Base on July 20th,

1942. Because of the importance of the stations, the army was put in charge

to defend them along with other important ports and cities across the country.

The Army's budget for fiscal year 1941 included a base near

Anchorage to cost $12,734,000, but Congress eliminated the item on April 4,

1940. A few days later, on April 9, Germany's armies invaded and occupied

Norway and Denmark. For the first time many members of Congress realized that

Norway and Denmark were just over the North Pole from Alaska and that the

Germans might soon have bombers that could fly that far. Congress restored the

money.

Before Japan entered World War II, its

navy had gathered extensive information

about the Aleutians, but it had no up-to-date information regarding military

developments on the islands. It assumed that the United States had made

a major effort to increase defenses in the area and expected to find several

U.S. warships operating in Aleutian waters, including 1 or 2 small aircraft

carriers as well as several cruisers and destroyers. Given these assumptions, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, Commander of the Japanese Combined Fleet, provided the Northern Area Fleet, commanded by Vice Admiral Boshiro Hosogaya, with a force of 2 small aircraft carriers, 5 cruisers, 12 destroyers,

6 submarines, and 4 troop transports, along with supporting auxiliary ships.

With that force, Hosogaya was first to launch an air attack against Dutch Harbor,

then follow with an amphibious attack upon the island of Adak, 480 miles to the

west. After destroying the American base on Adak (actually, there was none), his

troops were to return to their ships and become a reserve for two additional

landings: the first on Kiska, 240 miles west of Adak, the other on the

Aleutian's westernmost island, Attu, 180 miles from Kiska.

U.S. intelligence had broken the Japanese

naval code. Admiral Nimitz learned by 21 May of Yamamoto's plans, including the

Aleutian diversion, the strength of both Yamamoto's and Hosogaya's fleets, and

that Hosogaya would open the fight on 1 June or shortly thereafter. Nimitz decided to confront both enemy fleets, retaining his three aircraft carriers

for the Midway battle while sending a third of his surface fleet (Task Force

8) under Rear Admiral Robert A. Theobald to defend Alaska. Theobald was ordered

to hold Dutch Harbor, a small naval facility in the eastern Aleutians,

at all costs and to prevent the Japanese from gaining a foothold in Alaska.

Theobald's task force of 5 cruisers, 14 destroyers, and 6 submarines

quietly left Pearl Harbor on 25 May to take a position in the Alaskan Sea

400 miles off Kodiak Island, there to wait for the arrival of Hosogaya's fleet. On Theobald's arrival at Kodiak, he assumed control of the U.S. Army

Air Corps' Eleventh Air Force, commanded by Brigadier General (later Major General)

William C. Butler. This force consisted of 10 heavy and 34 medium bombers

and 95 fighters, divided between its main base, Elmendorf Airfield, in

Anchorage, and at airfields at Cold Bay and on Umnak. Theobald charged

Butler to locate the Japanese fleet reported heading toward Dutch Harbor

and attack it with his bombers, concentrating on sinking Hosogaya's two aircraft

carriers. Once the enemy planes were removed, Task Force 8 would engage

the enemy fleet and destroy it.

As of 1 June 1942, American military strength in Alaska stood at 45,000

men, with about 13,000 at Cold Bay (Fort Randall) on the tip of the Alaskan

Peninsula and at two Aleutian bases: the naval facility at Dutch Harbor

on Unalaska Island, 200 miles west of Cold Bay, and a recently built Army

air base (Fort Glenn) 70 miles west of the naval station on Umnak Island.

Army strength, less air force personnel, at those three bases totaled no

more than 2,300, composed mainly of infantry, field and antiaircraft artillery

troops, and a large construction engineer contingent, which had been rushed

to the construction of bases.

It was a dramatic time in Alaska's history...

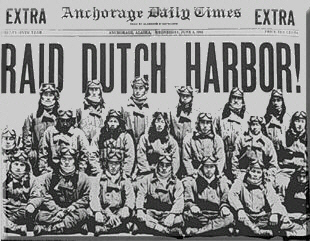

On the afternoon of 2 June a naval patrol plane spotted the approaching

enemy fleet, reporting its location as 800 miles southwest of Dutch Harbor. Theobald placed his entire command on full alert. Shortly thereafter bad

weather set in, and no further sightings of the fleet were made that day.

In the early morning

hours of June 3, 1942, despite dense fog and rough seas, Japanese carriers Junyo and Rynjo launched their planes for the attack on Dutch Harbor, less than 170

miles away. Unknown to the Japanese, however, their element of surprise

had been lost when the patrol plane had spotted them the previous day. The Japanese naval task force attacked the U.S.

base at Dutch Harbor on Unalaska Island in the Aleutian chain. The Japanese

attack was led by two aircraft carriers. Only half of the Japanese

aircraft reached their objective. The rest either became lost in the fog and

darkness and crashed into the sea or returned to their carriers. In all,

seventeen planes found the naval base, the first arriving at 0545. Fourteen

bombs fell on Fort Mears, destroying five buildings, killing 25 soldiers and

wounding 25 more. A second strike caused no damage, but a third damaged the

radio station and killed one soldier and one sailor. The

Americans were not fully prepared for an invasion, however they countered the attack with anti-aircraft and small arms

fire. The Japanese quickly released

their bombs, made a cursory strafing run on Dutch Harbor, and left to return to

their carriers. As a result of their haste they did little damage to the base.

The raid claimed 43 U.S. lives, of which 33 were soldiers. In the early morning

hours of June 3, 1942, despite dense fog and rough seas, Japanese carriers Junyo and Rynjo launched their planes for the attack on Dutch Harbor, less than 170

miles away. Unknown to the Japanese, however, their element of surprise

had been lost when the patrol plane had spotted them the previous day. The Japanese naval task force attacked the U.S.

base at Dutch Harbor on Unalaska Island in the Aleutian chain. The Japanese

attack was led by two aircraft carriers. Only half of the Japanese

aircraft reached their objective. The rest either became lost in the fog and

darkness and crashed into the sea or returned to their carriers. In all,

seventeen planes found the naval base, the first arriving at 0545. Fourteen

bombs fell on Fort Mears, destroying five buildings, killing 25 soldiers and

wounding 25 more. A second strike caused no damage, but a third damaged the

radio station and killed one soldier and one sailor. The

Americans were not fully prepared for an invasion, however they countered the attack with anti-aircraft and small arms

fire. The Japanese quickly released

their bombs, made a cursory strafing run on Dutch Harbor, and left to return to

their carriers. As a result of their haste they did little damage to the base.

The raid claimed 43 U.S. lives, of which 33 were soldiers.

The

next day the Japanese returned to Dutch Harbor.

This time the enemy pilots were better organized and better prepared. So

were the Americans. The Japanese pilots soon found themselves confronted by

U.S. fighter planes sent from Cape Field at Fort Glenn, a secret airbase on Umnak Island.

They had thought the nearest airfield was on

Kodiak, but Cape Field, disguised as a cannery complex, had remained undetected.

Aerial dogfights ensued. When the attack finally ended that

afternoon, the base's oil storage tanks were ablaze, part of the hospital was

demolished, and a beached barracks ship was damaged. Another 64 Americans were wounded. Eleven U.S. planes were

downed, while the Japanese lost ten aircraft. Following

these attacks, the Aleut people on the island were involuntarily evacuated to

safer locations in Southeast Alaska until their return in April 1945.

|

Buildings burning after the first enemy attack on Dutch Harbor,

3 June 1942.

(DA photograph) |

Since March 8, 1942, the Army and private

contractors had been constructing the Alaska-Canada Military Highway.

It took barely five months to build, the North and South crews meeting

(hence, completing the road) at Contact Creek that year on September 24.

The road was officially opened November 20th. This

was considered a major engineering achievement. The Alaska Highway (AlCan), as it is

now called, connected the landing fields on the air route to Alaska. It

started at Dawson Creek, British Columbia, and ran 2,288 km (1,390 mi) to

Delta Junction, Alaska. The road was for military use only until 1948

when it also opened to civilian traffic.

During the two-day fight, U.S. Task Force 8 had remained south of Kodiak

Island, taking no part in the action. Not until the 5th did Theobald send the

group to

investigate a report of enemy warships in the Bering Sea heading south toward

Unalaska Island.

While Task Force 8 entered the Bering Sea, Hosogaya's fleet moved south

to join Yamamoto, who had just suffered the loss of his four large carriers

off Midway. Unable to lure U.S. surface ships into range of his battleships,

Yamamoto ordered his fleet to return to Japan. Rather than have the Northern

Area Fleet join him, Yamamoto now instructed Hosogaya to return to

the Aleutians, execute his original mission, and thereby score a success

to help compensate for the Midway disaster. Forgoing the planned attack

on Adak, Hosogaya moved directly to the western Aleutians, occupying Kiska on 6 June and Attu a day later. He encountered no opposition on either

island, but the Japanese public was in fact told that this was a great

victory. It learned about the disaster at Midway only after the war was

over.

At Japanese Imperial Headquarters, the news of Yamamoto's great

loss prompted the dispatch of two aircraft carriers from Japan to reinforce Hosogaya. Having correctly anticipated Nimitz's next move - the dispatch,

on 8 June, of his two carriers to destroy Hosogaya's fleet - Imperial

Headquarters saw an opportunity to immobilize the U.S. Pacific Fleet

by eliminating its only carriers. When Nimitz learned of the capture of Kiska, he countermanded his order. Unwilling to risk the loss of his only

carriers in the Pacific to land-based planes from Kiska, and presumably

informed that Hosogaya would soon have four carriers at his disposal in

the North Pacific, he decided to retain his carriers for spearheading a

major advance in the Central Pacific.

For the Japanese, Kiska without Midway no longer had any value as a

base for patrolling the ocean between the Aleutian and Hawaiian chains,

but Kiska and Attu did block the Americans from possibly using the Aleutians

as a route for launching an offensive on Japan. Originally intending to

abandon the islands before winter set in, the Japanese instead decided

to stay and build airfields on both islands.

Supporting the possibility of an invasion of the Alaskan mainland were

reports of a Japanese fleet operating in the Bering Sea. On 20

June alone, three separate sightings placed an enemy fleet somewhere

between the Pribilof and St. Lawrence Islands, suggesting that either an

enemy raid on or an outright invasion of the Alaskan mainland was imminent,

with Nome the likely objective. As a result, a sense of urgency bordering

on panic set in that triggered what was to become the first mass airlift

in American history. Within thirty-six hours, military as well as commandeered

civilian aircraft flew nearly 2,300 troops to Nome, along with artillery

and antiaircraft guns and several tons of other equipment and supplies.

Not until early July - when U.S. intelligence reported with some certainty

the departure of Hosogaya's fleet from the Bering Sea - did the threat of

invasion of the Alaskan mainland decline, allowing for the redeployment

of many of the troops hastily assembled at Nome.

In keeping with the Joint Chiefs' desire to move quickly to regain Kiska and Attu, Theobald and Buckner agreed to establish a series of airfields

west of Umnak from which bombers could launch strikes against the closest

of the enemy-held islands, Kiska. First to be occupied was Adak, 400 miles

from Umnak. Landing unopposed on 30 August, an Army force of 4,500 secured

the island. Engineers completed an airfield two weeks later, a remarkable

feat that they were to duplicate again and again throughout the campaign.

On 14 September U.S. B-24 heavy bombers took off from Adak to attack Kiska,

200 miles away. Repeated bombings of Kiska during the summer and into the

fall convinced the Japanese that the Americans intended to recapture the

island. As a result, by November they had increased their garrisons on Kiska and Attu to 4,000 and 1,000 men respectively. During the winter months

the Japanese would count on darkness and the habitually poor weather to

protect them from any serious attack.

Just surviving the weather on Amchitka was a challenge. During the first

night ashore, a "willowaw" (a violent squall) smashed many of the landing

boats and swept a troop transport aground. On the second day a blizzard

racked the island with snow, sleet, and biting wind. Lasting for nearly

two weeks, the blizzard finally subsided enough to reveal to a Japanese

scout plane from Kiska flying along the American beachhead on Amchitka. Harassed by

bombing and strafing attacks from Kiska, engineers continued work on an

airfield on Amchitka completing it in mid-February. Japanese attacks on

the island then sharply declined.

As U.S. forces came close to Kiska and Attu, the enemy's outposts became

increasingly more difficult to resupply. On March 26th, Rear Admiral Thomas

C. Kinkaid, who had replaced Admiral Theobald in January, established a

naval blockade around the islands that resulted in the sinking or turning

back of several enemy supply ships. When a large Japanese force, personally

led by Admiral Hosogaya, attempted to run the blockade with 3 big transports

loaded with supplies and escorted by 4 heavy cruisers and 4 destroyers on 26

March, the largest sea fight of the Aleutian Campaign took place, remembered

best as the last and longest daylight surface naval battle of fleet warfare.

Known as the

Battle of the Komandorski Islands, the closest land mass in the Bering Sea,

the Japanese ships were repulsed with heavy losses. The smaller U.S. force

had compelled Hosogaya to

retire without completing his mission and resulted in his removal from

command. Henceforth, the garrisons at Attu and Kiska would have to rely

upon meager supplies brought in by submarine.

Of the two islands, Kiska was the more important militarily

since it held

the only operational airfield and had the better harbor. Kiska was scheduled

to be recaptured first. For that purpose Kinkaid, Commander of Northern

Pacific Force, asked for a reinforced

infantry division (25,000 men). When not enough shipping could be made

available to support so large a force, he recommended that Attu be substituted

for Kiska as the objective, indicating that Attu was defended by no more

than 500 men, as opposed to 9,000 believed to be on Kiska. If the estimate

was correct, he indicated, he would require no more than a regiment to

do the job. Kinkaid also noted that U.S. forces based on Attu would be

astride the Japanese line of communications and thus in a position to cut

off Kiska from supply and reinforcement, which in time would cause Kiska to "wither on the vine."

After gaining approval on April

1st for the Attu operation and obtaining the needed shipping, work began to recapture the

fog-enshrouded island at the western end of the Aleutian chain. Kinkaid pulled together an

imposing armada to support an invasion. In addition to an attack force

of 3 battleships, a small aircraft carrier, and 7 destroyers for escorting

and providing fire support for the Army landing force, he had 2 covering

groups, composed of several cruisers, destroyers, and submarines, for early

detection of a possible challenge by the Japanese Northern Area Fleet.

Reinforcing the naval support, the Eleventh Air Force was to provide 54 bombers

and 128 fighters for the operation, holding back a third of the bomber force for

use against ships of the Japanese fleet.

Early in the planning phase, U.S. intelligence upgraded the

estimated enemy strength on Attu threefold from its original figure of 500 men,

prompting a request for additional forces. Buckner had just a single

infantry regiment in Alaska, widely dispersed throughout the territory.

The War Department provided the needed troops from DeWitt's Western Defense

Command, selecting the 7th Infantry Division (7th ID), then stationed near Fort Ord, California, as the unit to recapture Attu. In April 1943, after

completing amphibious training required for its new mission, the 7th ID embarked

from San Francisco on transports with their commander, Major General Albert E.

Brown.

Arriving at windswept, but snow-covered, Fort Randall (Cold Bay)

on the 30th, the troops spent the next four days on the crowded transports.

The cold, damp Aleutian weather was far different from the warm California

beaches they had just left. Because of shortages in cold weather equipment,

moreover, most of the men entered combat wearing normal field gear.

While senior commanders realized that the troops would suffer from the

weather, most believed that within three days the fight for Attu would

be over, particularly since the assembled naval support for the landings

included three battleships along with several cruisers and destroyers.

Despite unremitting fog, the assault opened on 11

May at four widely separated points on the eastern portion of the island. When

General Brown came ashore at Massacre Bay toward the end of the day, the

tactical situation was far from clear, but what information was available would

not have indicated that a long drawn-out struggle was in prospect. By 9:30 p.m., five

hours after the main landings commenced, he had a total of 3,500 men ashore; 400

at Beach SCARLET, 1,100 at Beach RED, and 2,000 at Beaches BLUE and YELLOW. On

the northern front, the 1st Battalion was close to Hill X and within twenty-four hours the 32d Regiment,

with its 1st and 3d Battalions, was due to arrive from Adak. In the southern

sector, the 2d Battalion of the 17th reported that it was within 1,000 yards of Sarana Pass, and the 3d Battalion indicated that it was about 600 yards short of Jarmin Pass. The next day, the 2d Battalion, 32d Regiment, on ship in Massacre

Bay, was to come ashore to reinforce the 17th Regiment. If additional forces

were needed, General Buckner had agreed to release the 4th Infantry Regiment, an

Alaska unit, on Adak Island. Everything considered, it would not have been

unreasonable to suppose that within a few days Attu would be taken. Battalion was close to Hill X and within twenty-four hours the 32d Regiment,

with its 1st and 3d Battalions, was due to arrive from Adak. In the southern

sector, the 2d Battalion of the 17th reported that it was within 1,000 yards of Sarana Pass, and the 3d Battalion indicated that it was about 600 yards short of Jarmin Pass. The next day, the 2d Battalion, 32d Regiment, on ship in Massacre

Bay, was to come ashore to reinforce the 17th Regiment. If additional forces

were needed, General Buckner had agreed to release the 4th Infantry Regiment, an

Alaska unit, on Adak Island. Everything considered, it would not have been

unreasonable to suppose that within a few days Attu would be taken.

The next day, with naval and air support, Brown's men continued their

two-pronged attack toward Jarmin Pass. Frontal assaults from Massacre Bay by the

17th Infantry failed to gain ground. As patrols probed to develop enemy

positions, the 2d Battalion, 32d Infantry, came ashore at Massacre Bay. In the

meantime, in the northern sector, the 1st Battalion, finding the enemy dug in on

Hill X, made a double envelopment which succeeded in gaining a foothold on the

crest of the hill, but the Japanese held firm on the reverse slope. That night

the first casualty report of the operation revealed that 44 American troops had been killed since the start of the

invasion.

Further efforts of the Massacre Bay force on the 13th to gain Jarmin Pass again failed, even with the 2d Battalion, 32d Infantry, entering the

fight to reinforce the 3d Battalion, 17th Regiment. As U.S. losses continued

to mount, front-line positions remained about the same as those gained

two days prior. Vicious and costly fighting occurred to the north as the enemy

attempted to drive the 1st Battalion troops from Hill X, but the crest

remained firmly in American hands at nightfall. The 3d Battalion, 32d Regiment,

by then had landed on Beach RED and was moving forward to reinforce the

hard-pressed 1st Battalion on Hill X. Naval gunfire and air support of

the ground troops continued insofar as weather conditions allowed.

Weather as well as the enemy continued to

frustrate the American advance. Each attack quickly bogged down. Although

surface ships continued to bombard reported enemy positions ashore on the 14th,

close air support was extremely limited due to incessant fog that engulfed the

island.

The next morning, June 15th, the fog lifted in the northern sector, revealing that the enemy had withdrawn

to Moore Ridge in the center of Holtz Valley, leaving behind food and ammunition.

As American troops entered the valley in chase, the relatively

clear sky allowed the Japanese occupying Moore Ridge to place accurate

fire upon them.

Back on Adak, the forward command post for Admiral Kinkaid and General

DeWitt, the reported situation at Attu appeared grim. Of special concern

to Kinkaid was the exposed position of the ships directly supporting Brown's

forces ashore. A Japanese submarine had already attacked (unsuccessfully)

one of Kinkaid's three battleships, and reports persisted that a Japanese

fleet would soon arrive to challenge the landing. As a result, Brown was

told that the Navy would withdraw its support ships on the 16th, or in

any event no later than the 17th, leaving him with an unprotected beachhead

and a major reduction in supporting fire.

Brown had bogged down. When Kinkaid consulted

with DeWitt and Buckner, both agreed with him that Brown should be replaced.

Upon their recommendation, Kinkaid appointed Major General Eugene M. Landrum

to take command of Attu on the 16th.

An advance by the Northern Landing Force broke the deadlock on Attu the same

day Landrum assumed command. By then a foothold on the northern end of

Moore Ridge had been won in the center of Holtz Valley, thereby gaining

control of the entire ridge. The Japanese, greatly outnumbered by the Americans

and in danger of being taken from the rear, withdrew that night (16-17

May) toward Chichagof Harbor for a final stand.

Well before dawn, troops controlled by the 32d Regiment in the northern

sector moved forward and by daylight discovered that the enemy had gone.

Patrols reported that the east arm of Holtz Bay was free of the enemy,

allowing for much-needed resupply by sea. In the meantime, the 17th Regiment

in the southern sector (at Massacre Valley) also found previously defended

enemy positions abandoned, and it occupied Jarmin Pass.

The Japanese pullback to Chichagof Harbor followed by the linkup of

U.S. forces on the 18th provided the turning point of the battle. While

nearly another two weeks of hard, costly fighting remained, the uncertainty

and frustration of the first few days on Attu never recurred. It was slow

business taking the machine-gun and mortar nests left manned on the heights

by the retreating Japanese, but eventually the combined American force, reinforced with a battalion

of the 4th Infantry, drew a net around Chichagof Harbor. The end came on

the night of 29 May when most of the surviving Japanese, about 700 to 1,000

strong, charged madly through American lines, screaming "Banzai," killing, and being

killed. The next day the enemy announced the loss of Attu, as American

units cleared out surviving enemy pockets. Although mopping-up operations

continued for several days, organized resistance ended with the wild charge

of 29 May, and Attu was once more in American hands.

The Americans reported finding 2,351 enemy dead on the island; an additional

few hundred were presumed to have been buried in the hills by the Japanese.

Only 28 Japanese surrendered. Out of a U.S. force that totaled more than

15,000 men, 549 had been killed in combat, another 1,148 wounded, and about 2,100

men taken out of action by

disease and non-battle injuries.

Attention was now turned to Kiska Island...

Starting in late July 1943, most pilots reported no signs of enemy activity

on the island, although a few noted that they had still received light

antiaircraft fire. These reports led intelligence analysts to conclude

that the Japanese on Kiska had been evacuated or had taken to the hills. Convinced that the later

contention was more probable, Kinkaid ordered the attack to take place

as scheduled, noting that if the Japanese were not there the landings would

be a "super dress rehearsal, good for training purposes," and the only

foreseeable loss would be a sense of letdown by the highly keyed up troops.

Stung by the brutal fight for Attu, Admiral Kinkaid sought to avert

the same mistakes at Kiska. While the full-blown attack three months later

upon the deserted island was an embarrassment, the detailed preparation

for Kiska was worth the effort. Kinkaid ensured that the

final assault in the Aleutians, against Kiska, would be made with

better-equipped and more seasoned soldiers. For the coming invasion his assault troops

wore clothing and footwear better suited for the cold weather; parkas

were substituted for field jackets and arctic shoes for leather boots.

The landing force consisted of either combat veterans from Attu or

troops trained at Adak in the type of fighting that had developed on Attu.

U.S. intelligence now upgraded its earlier estimates of enemy strength

on Kiska to about 10,000 men. In keeping with that increase, Kinkaid arranged

for his ground commander, Major General Charles H. Corlett, U.S. Army, to receive

34,426 troops, including 5,500 Canadians, more than double the original

strength planned for the operation earlier in the year. The operation was to begin on 15

August, onto an island 3 to 4 miles wide

with a high, irregular ridge dividing its 22-mile length and with a defunct volcano at its northern end. The Japanese had occupied only the central, eastern

portion of the island, locating their main base and airfield at Kiska Harbor.

They also had small garrisons on Little Kiska Island and south of the main

harbor at Gertrude Cove. August, onto an island 3 to 4 miles wide

with a high, irregular ridge dividing its 22-mile length and with a defunct volcano at its northern end. The Japanese had occupied only the central, eastern

portion of the island, locating their main base and airfield at Kiska Harbor.

They also had small garrisons on Little Kiska Island and south of the main

harbor at Gertrude Cove.

Unlike Attu, Kiska was subjected to heavy pre-invasion bombardment.

Reinforced during June and operating from new airfields (at Attu and nearby Shemya), a combined air and surface bombardment

continued into August, interrupted only by bad weather.

Departing Adak, the staging area for the invasion, an amphibious force

of nearly a hundred ships moved toward Kiska, reaching the island early

on 15 August. Unlike the dense fog experienced at Attu, the seas were strangely

calm and the weather unusually clear. By 4 p.m. a total of 6,500

troops were ashore. The next day Canadian troops came ashore onto another

beach farther north. As with the fight for Attu, the landings were unopposed.

As Allied troops pushed inland, the weather returned to the more normal

dense fog and chilling rain and wind. Veterans of the Attu campaign, in

particular, expected that the enemy was waiting on the high ground above

them to take them under fire.

The Allies had attacked an uninhabited island. The entire enemy garrison

of 5,183 men had slipped away unseen. The Japanese evacuation of Kiska had

been carried out on 28 July, almost three weeks before the Allied landing. The only guns that were fired were those of friend against

friend by mistake; partly on that account, casualties ashore during the

first four days of the operation numbered 21 dead and 121 sick and wounded.

The Navy lost 70 dead or missing and 47 wounded when the destroyer Amner Read struck a mine on 18 August. By the time the search of the island,

including miles of tunnels, ended, American casualties totaled 313 men.

On 24 August 1943, General Corlett

declared the island secure, marking the end of the Aleutian Islands Campaign. By

year's end, American and Canadian troop strength in Alaska would drop from a

high of about 144,000 to 113,000. By then the North Pacific Area had returned to

complete Army control. During 1944 the Canadians would leave and U.S. Army

strength in the Alaska Defense Command decrease to 63,000 men. Although interest

in the theater waned, it was in the Aleutians that the United States won its

first theater-wide victory in World War II, ending Japan's only campaign in the

Western Hemisphere.

It is here I'll inject a few final, but

important, notes on the subject:

-

Some 1,067 Allied military men and women died, were

captured or were interned in the campaign to liberate the Aleutians.

-

The Japanese soldiers who occupied the Aleutian islands of Attu and Kiska become the first foreign invaders to occupy American soil since the War of

1812.

-

The Aleutians saw cold-weather fighting that was bitter and

protracted, and largely ignored by the American public.

-

The centerpiece of the

Aleutian Campaign was the battle for Attu. In terms of numbers engaged, Attu ranks as one of the most costly assaults in the Pacific.

For every 100 enemy found on the island, about 71 Americans were killed

or wounded. The cost of taking Attu was thus second only to Iwo Jima.

|

|

|

Aleutian Cemetery, Attu Island |

The war years irrevocably changed Alaska,

leaving a profound and lasting impact on the territory. It

altered the pace of Alaskan life. In 1940, about 1,000 of Alaska's 75,000

residents were military. By 1943, 152,000 out of 233,000 belonged to the armed

forces stationed in Alaska. Between 1941 and 1945 the federal

government spent close to $2 billion in the north. The modernization of the

Alaska railroad and the expansion of airfields and construction of roads

benefited the war effort as well as the civilian population. Many of the docks,

wharves, and breakwaters built along the coast for the use of the U.S. Navy,

Coast Guard, and Army Transport Service were turned over to the territory after

the war. Most importantly, thousands of soldiers and construction workers had

come north, and many decided to make Alaska their home. Between 1940 and 1950

the civilian population increased from 74,000 to 138,000. The

sparse population could no longer be used as an excuse to deny Alaska her statehood.

|

Dutch Harbor: The Japanese first attacked Alaska at this location on

June 3, 1942.

Unmak: Although the Americans had a seaplane base at Dutch Harbor, they

built their first air field capable of handling wheeled aircraft in the Aleutians

on this island.

Attu: Several days after their attack on Dutch Harbor the Japanese landed

on Attu and took control of the island. On May 11, 1943 the Americans launched

a massive attack against the Japanese on Attu. It took 3 weeks for the Americans

to defeat the Japanese.

Kiska: The Japanese' primary invasion force was on the island of Kiska.

They evacuated Kiska on July 28, 1943.

Adak: The U.S. built an air base on this Aleutian island in September

1942 to provide closer access to Kiska and Attu.

Cold Bay: This Alaska Peninsula town was the base for exchange of ships

and supplies with the Soviet Union for the war with the Germans.

Fairbanks (not shown): Located in central Alaska, this town became the base for

American and Soviet exchange of 8000 aircraft.

|

|